thread for posting musical thoughts

Words, pictures, sound recordings, videos. This thread is for when you want to wonderpost a specific musical idea -- not just a whole song.

(Meteor Light)

(Meteor Light)

Tagged:

Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Comments

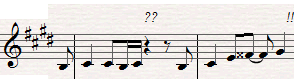

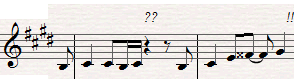

Using double-sharps and double-flats is just an extension of this principle to something that's already sharped. Going with the F# to G example, let's say we were in C# lydian/major. The F is already sharped, so just slap a double-sharp onto it, so it still looks right on paper: Fx to G#.

At least, that's what I think.

Like, for example, the beginning of the Duck Tales theme, or the Super Mario World credits theme, or the refrain part of COOL & CREATE's "Help Me, Erin!", or the Battletoads pause music? Usually, this is accompanied by a desire to make a very forced, very toothy, grin while otherwise appearing constipated.

stop being so piano-centric

And yeah, a violinist friend to me that for him, D# is actually a little more sharp than Eb. Of course, he can get away with it with fretting. As a keyboardist, however, I don't have much choice in the matter...

...yes, that pun was indeed intentional.

Assassin poems, Poems that shoot

guns. Poems that wrestle cops into alleys

and take their weapons leaving them dead

also by "submediant" you mean "supertonic" (scale degree 2) since "submediant" is used to refer to scale degree 6

^ well, it by default covers about 400 years worth of music that's recognized around the world, and with a few small extensions you can cover much of modern non-folk music too. It's not perfect but I'd argue that it's a good start.

That said, it isn't perfect, especially when it comes to subdivisions of the octave into more or fewer than 12 notes (or some factor of it). And there's a lot of folk styles that get into what western theory would consider odd tuning styles, stuff like quarter-tones and whatnot.

Rhythm, on the other hand, seems to be pretty well set. Probably because we all have two feet and stuff.

(it's from Symphogear, specifically one of the OST tracks)